Pretty much the entire diabetes clinical world in the UK must now be aware of what the Freestyle Libre is, and that it was added to the NHS BSA prescribable list at the beginning of November 2017.

Nearly all interested patients will also know that for much of 2018 it has been completely unavailable in most of England, and with a little more than a month to go till the year’s anniversary of being prescribable, there are still swathes of the country where it is either totally unavailable or the criteria that have been put in place are so restrictive that it makes it effectively unavailable.

Rather than go into the detail of the roll out across the UK, which Nick Cahm has covered in great detail, I’m going to take a look at a specific part of the country that, in theory, was putting in place an approach that would be applicable across an entire region. And how it has failed.

London. The city where I live and the one covered by multiple CCGs and rather than a London wide approach to prescribing, grouping regionally within London, roughly by geographic area.

This becomes interesting when you look at how Libre adoption has been handled. In October/November last year, each prescribing area, or more precisely, each Area Prescribing Committee issued guidance to NOT prescribe Libre until a London wide position was put in place. This seems fairly logical, and the right approach to take.

The Regional Medicines Optimisation Committee (Northern) starting point for ALL implementation guidance (issued in October 2017) states that:

It is recommended that Freestyle Libre® should only be used for people with Type 1 diabetes, aged four and above, attending specialist Type 1 care using multiple daily injections or insulin pump therapy, who have been assessed by the specialist clinician and deemed to meet one or more of the following:

1. Patients who undertake intensive monitoring >8 times daily

2. Those who meet the current NICE criteria for insulin pump therapy (HbA1c >8.5% (69.4mmol/mol) or disabling hypoglycemia as described in NICE TA151) where a successful trial of FreeStyle Libre® may avoid the need for pump therapy.

3. Those who have recently developed impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia. It is noted that for persistent hypoglycaemia unawareness, NICE recommend continuous glucose monitoring with alarms and Freestyle Libre does currently not have that function.

4. Frequent admissions (>2 per year) with DKA or hypoglycaemia.

5. Those who require third parties to carry out monitoring and where conventional blood testing is not possible.

In addition, all patients (or carers) must be willing to undertake training in the use of Freestyle Libre® and commit to ongoing regular follow-up and monitoring (including remote follow-up where this is offered). Adjunct blood testing strips should be prescribed according to locally agreed best value guidelines with an expectation that demand/frequency of supply will be reduced.

—————————————————————————————————————-

The RMOC is aware that clinics using Freestyle Libre® are already collecting audit data and would strongly support all clinics to work collaboratively (potentially through the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists) to maximize learning about this new intervention and measure its impact in individual patients.

We suggest information is collected on the following:

1. Reductions in severe/non-severe hypoglycaemia

2. Reversal of impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia

3. Episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis

4. Admissions to hospital

5. Changes in HbA1c

6. Testing strip usage

7. Quality of Life changes using validated rating scales.

8. Commitment to regular scans and their use in self-management.

We recommend that if no improvement is demonstrated in one or more of these areas over a 6 month trial then the use of Freestyle Libre® should be discontinued and an alternative method of monitoring used.

Source: RMOC (Northern) position statement October 2017: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Flash-Glucose-monitoring-System-RMOC-Statement-final-2.pdf

This is a subset of the statement, but clearly identifies:

- The initiating clinician is from Secondary Care (specialist clinician)

- The set of criteria which makes you eligible, of which only one needs apply

- Measures that demonstrate whether the Libre is valuable and should be continued

That’s a large amount of the hard work done and done in October 2017, before it was possible to get the Libre on Prescription. It should have been simple, at a national level, to then create the training and competency sheets and share them across NHS England and Wales.

Instead we have the ludicrous position where each regional group, in one way or another, is doing its own thing, creating its own documents and training and generating additional criteria, all with varying timings and viewpoints. Manchester managed to get implementation guidance out in November 2017, pretty much restating the above. How much money has been wasted in the interim as others have taken on this process?

So going back to London.

The London Diabetes Clinical Network (LDCN) in partnership with the London Procurement Partnership (LPP) went away and spent six months putting together guidance and documentation that looks remarkably similar to the RMOC guidance (much of which was really already available from that October 2017 statement and Manchester’s policy). This provides the following documents:

- Implementation Guidance

- Primary Care information sheet

- Recommended Competencies for Initiating Clinicians

- Recommended Competencies for patients

- Recommended Competencies for continuing prescribers

- Training pack for HCPs and Patients

- Community Pharmacy Information Sheet

If you look through them, the first question you may be tempted to ask is “Why did it take six months to produce this?”. Moving on….

… these were all published on 1st May 2018 and and then what happened was the local areas picked these documents up and followed the recommendations to make Libre available, so now it’s widely available in London. Right?

Wrong.

That’s not what has happened, because the approach is not a “London Wide” set of rules that must be followed…

What do I mean? The approach that London has taken is to have an NHS QuaNGO that sits over the top of all the regional, fund holding, bodies within London, made up of representatives of all of them, put together a set of documents that is not binding for any of them and no-one has to pay any attention to.

You what? Did I hear you correctly? Yes you did, and this is covered within the implementation guide itself…

We hope this implementation guidance will be universally adopted across the region to ensure equity of access for patients in London. The process of approval will vary depending on local pathways but organisations are encouraged to include their local clinicians in discussions to facilitate local implementation. This document is a comprehensive guide, designed so that sections can be removed and used in practice, as and when appropriate. Further supplementary documentation will be provided as detailed on the first page.

If these recommendations are accepted, local committees should confirm within their networks the process for initiation and prescribing and are recommended to liaise with the clinical networks in regards to organising training.

So, London has spent six months writing a set of RMOC based implementation guidelines and training that no-one at the CCG or Area Prescribing Committee (APC) is bound to follow. And each of those individual APCs has no obligation NOT to make changes to the London wide “guidance”.

Wow!

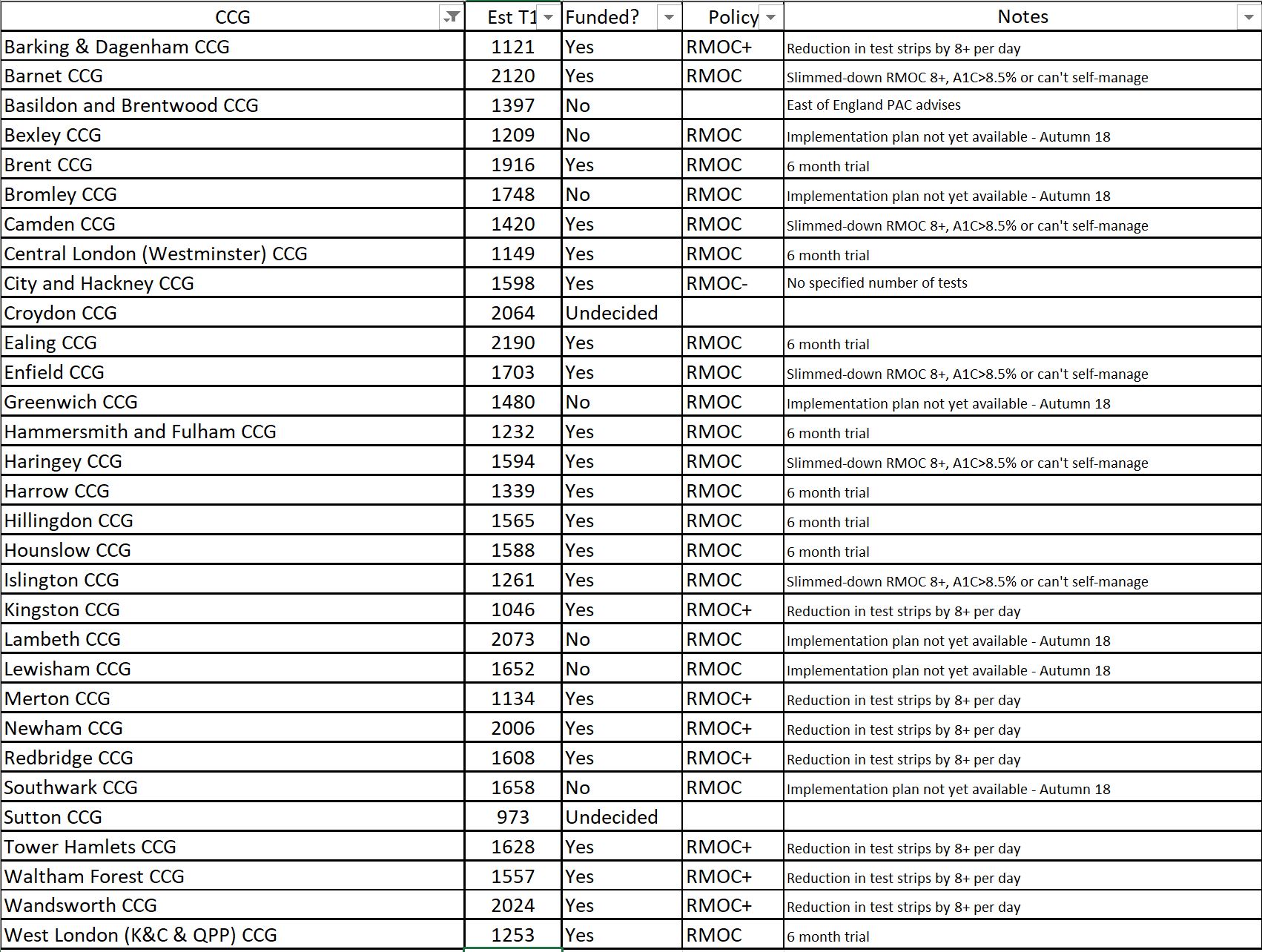

We’re seeing this very clearly in the roll out of Libre across London, where some of the APCs have already released their guidance to make Libre available, although they have made changes to the “London guidance” (for example, North West London), whilst others haven’t even completed their own “implementation plan” (I’m talking about you, South East London APC/Medicines Optimisation Committee), despite already being provided with a comprehensive one. If we look at the table below, we can see the variance from the original RMOC statement I’ve given above, and the variation between CCGs in London alone.

To add some context to this, those London guidelines I mentioned earlier were issued to APCs and CCGs earlier than 1st May 2018. Wandsworth published a guide to training for Libre prior to 1st April 2018, which is thorough and provides details of all the appropriate people to contact, but of course it was only issued in Wandsworth CCG.

Why do you care about Libre or South East London?

I care about Libre because it and other forms of CGM are a real game changer in living with type 1, but are sadly far too expensive for most people to afford, so this dramatically changes the access for most, and South East London, because I live there.

As a result of some vague position statements from the South East London Area Prescribing Committee I got in touch to ask what was going on, as the guidance is clear. If you weren’t aware, the APC responds like PALS (the liaison and complaints group) so any question will take 25 working days to get a response (although they claim less time when it’s not the holiday period).

This was their response:

We have a responsibility to ensure that processes are in place across primary and secondary care for safe and effective prescribing.

As outlined in our SEL Area Prescribing Committee (APC) position statement dated July 2018, at this current time flash glucose monitoring is not recommended for prescribing in South East London until mechanisms have been put in place to support delivery of the local implementation plan. We have been working hard on our local implementation plan to ensure the safe and effective introduction of FreeStyle Libre in SEL. This includes work on these elements of our local implementation plan;

• Training of all relevant healthcare staff on the use of Freestyle Libre,

• Agreement on the responsibilities and process for assessment, initiation, review, audit, patient education and ongoing prescribing of flash glucose between all our hospitals and general practices for adults and children,

• Consistent communication including a patient/prescriber agreement, transfer of care documents and local patient information leaflets.

Thank you for raising the issue of training in your email. When signing a prescription for flash glucose monitoring sensors, the clinician takes full responsibility for the prescription issued. Therefore we need to ensure all clinicians who will be reviewing and/or prescribing flash glucose devices (for new or existing patients using FreeStyle Libre) are trained appropriately on the use of the device. When reviewing the current position across SEL, we have identified a training need for many secondary care and primary care colleagues in the use of FreeStyle Libre as they will be required to assess and prescribe. The APC feel that this is an essential part of ensuring safe and effective prescribing and needs to be in place before prescribing on the NHS can occur. We can reassure you that plans are in place across SEL for training relevant members of the team, using the London Diabetes Clinical Network recommended training options, and will be in place for the Autumn time frame outlined in our position statement.

We are working very closely with the London Procurement Partnership (LPP) and London Diabetes Clinical Network to make sure that we share resources and experience. The APC have set a deadline of Autumn 2018 to fully implement flash glucose monitoring in SEL and we are on track to meet this deadline.

So, why has it taken to here to post this email? If we dig into it, there are a number of statements that might raise eyebrows, given some of the other things I’ve pointed out in this post.

- Who is responsible for what? – Clearly described in the initial October 2017 statement, so why does it take agreement to redefine this in South East London?

- Training – again, other parts of London had clear training plans published in early 2018 and showing how it would be done within 3 months of the Libre hitting formularies

- Working closely with LPP and LDCN to share resources and expertise – yet not closely enough to know about other APCs providing training plans, having training materials available from the beginning of May and understanding the clearly defined responsibilities (and training process) from existing documents.

Finally, the additional point that raises eyebrows is the statement about patient/prescriber agreement, transfer of care documents and local patient information leaflets.

Lets start with the last of these. What’s different about a patient information leaflet in South East London compared to one in Manchester, apart from some phone numbers, names and identity? Why is something new needed when it could all have been reused? This is the least contentious point.

Transfer of care documents. How do these differ for Libre from Secondary to Primary care, to a pump, or a CGM, or a prescribed drug? The process and required docs should be the same. This should not be created as a wholly new process.

Patient/prescriber agreements. This is by far the most contentious point on this list. Where do we require people prescribed glucose lowering drugs to sign an agreement between themselves and the prescriber, saying that if their glucose levels are not reduced, they will give the drugs back, or change to an inferior treatment?

As an example, Trulicity 1.5mg/0.5ml costs £73.25 per four pens. One pen lasts a week, therefore they cost at least £73.25 per month. This is more than a Libre, but no patient/prescriber agreement is required.

Why does Libre (technology) require something different from drugs in this context?

What can we take away from this?

It’s not really about South East London in particular. They are just the focus here because they present an obvious and clear case study. We already know that there is a postcode lottery in place and the example of London shows why. The only conclusion that I can draw it that it comes down to a series of factors:

- Each area wants to do their own thing on something that national guidance should be good enough for. T1D doesn’t change based on postcode, so why should access to treatment that has proven to change lives and guidance around it?

- What is the additional expertise that the local areas have over the national specialists that means that they know better?

- As each area wants to do their own thing, they commit resources to develop pan-area and local area versions of the same thing that have very few differences and a lot of similarities, usually generating exclusions to reduce costs. If the national guidance were adopted in the first place, those local resources wouldn’t have been needed to spend time, and importantly, budget, on investigations, additional guidelines and processes, that could have been put back into treatment.

- By fiddling, prevaricating and pushing out the point at which decisions are made and additional treatments are added to the formulary, costs can be avoided on the balance sheet.

- The NHS has very little idea how to deal with technology as a mechanism for better treatment in long term conditions.

As you look back at this, you get the feeling that often, the patient isn’t at the heart of the process. Whilst I understand that cost plays an important part, that’s accounted for in the criteria that were originally published in October 2017 and is no different to the roll out of any other treatment.

What London and the Libre demonstrate is that regardless of regional approaches to delivery of treatments like the Libre, the NHS operates at a local level, and this overrides any National lines. If a corporate were to operate like the NHS does, its shareholders would be firing the CEO and management team and replacing it.

When Libre was first added to the BSA list, there was a request from NHS England to take a common approach to reuse assets and take a collaborative approach. The more you look at this data, the less it appears to be the case.

Duplication of effort at multiple levels, “I know better than you” attitudes and significant use of resource in an unnecessary way shouldn’t be ignored. It’s no wonder that we see so much variation, not only in availability of Libre, but in Diabetes care in general.

It would appear that, in this case at least, we don’t have a very National health service.

Nice article. Neuropad is also on the NHS Tariff and has been since before #Flash. Because we don’t have a large field force like big pharma we chose to put it through NHS England’s very own Innovation Accelerator, known as the NIA. They say that Neuropad is a ‘great innovation’ and that it is ‘a good, patient-centred innovation that has the potential to improve screening for foot problems in people with diabetes and therefore reduce preventable foot ulceration and amputation, which are expensive for the NHS and devastating for patients.’ Significantly, ‘clinical assessors were strongly in support of this innovation.’ Wow! It doesn’t get any better than that. We also pitched Neuropad to NICE and their Medical technology Evaluation Programme people assessed it, wrote a long scoping report which they presented to the NICE MTEP committee who then decided to route neuropadn for guidance development which is about as good as it gets. So, almost at the same time in 2016 we had NHS England and NICE saying positive things about Neuropad. Now the bad news. Though the NIA say that Neuropad is a ‘great innovation’ etc they have no power to introduce anything to the NHS in any meaningful way and what have they done to help us get Neuropad established? Nothing. Meanwhile, NICE took 108 weeks to develop their woeful Neuropad guidance which has more holes in it than a Swiss cheese (sorry Switzerland). NICE even state that Neuropad is a replacement for 10g monofilament testing which it is not. We have never said that it is – this is their own fantasy. We spent many months trying to get them to rectify this monumental error they just wouldn’t listen. NG28 was a total fiasco at the time and you would have thought that they would have learned something but it is clear that they have not. Mind you, it appears that Pulse, if not most of the medical profession think that NICE guidelines and guidance is very often ‘bonkers’ and it is clear that CCGs, GP federations and hospital trusts don’t may much attention to it anyway so maybe our journey through NICE would have been (and is) a pointless exercise. Currently, we have a useful test for the much earlier detection of diabetic neuropathy when it is possible to halt and in some cases reverse small nerve fibre damage, which is not the case with large nerve fibre damage which is irreversible, buit it seems that at the moment the only people benefiting from it are those that can afford to pay for it which it strikes me is what the NICE and the NHS are happy to condone. This is discriminatory. Indeed, there are 500,000 people with diabetes who never have an annual foot check, effectively leaving them at the mercy of ulceration and eventual amputation when there is a simple test that can be posted to them at home. This is scandalous in my opinion. If we don’t get to grips with screening and add Neuropad to sensory testing to improve its positive and negative predictive value which enables a proper, evidence-based risk stratification to be implemented the current nationally disgraceful diabetes related amputation rate (169/wk) will just climb relentlessly higher. So, it’s not just widespread access to #Flash that’s needed but to our #tenminutetest also. In fact, our healthcare economic model shows that very substantial savings can be made by adding it to 10g monofilament testing which might also pay for Libre sensors. What we need is some joined up thinking which seems in very short supply in the NHS, the DoH and NICE.